Mystic Union Of The Sublime Order

Or why some of us are inclined to all things dark and melancholic in times of push-and-pull dynamics and way too much suffering

When I first started writing this piece, I was alone in a cabin in the middle of a snowy Swedish forest. I was contemplating what my life is going to be like this year. It’s not the first time I die and am reborn, but it’s always painful. And yet, despite the skin that is shed, there is something in my core that remains true: my tendency to all things intense, dramatic, melancholic, dark.

It’s not simply a matter of taste, an identification with a subculture, or an inclination to a certain aesthetic. These are all parts of a bigger whole. Though I could describe myself through a list of keywords that reflect my profession, my nationality, my gender, or my psychiatric diagnosis, what matters here is something else.

I am talking about how I do not take things lightly and how “my” very things cannot be light either. They need to match my freak; they need to be sanguine, funereal, obscure, profane, occult, melodramatic, sublime.

On the sublime

Though the word, when colloquially used, may sound like a synonym for something beautiful, it has acquired another sense after Edmund Burke published A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful in 1757. In this work, he describes the sublime as:

Whatever is fitted in any sort to excite the ideas of pain and danger, that is to say, whatever is in any sort terrible, or is conversant about terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogous to terror, is a source of the sublime; that is, it is productive of the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling.

Burke mentions pain in the sense that it is a “much more powerful [feeling than]… pleasure”, despite not being, you know, pleasant. He also adds that, commonly, we equate intense pain with the idea of death, which is, by its part, “a much more affecting idea; because there are very few pains, however exquisite, which are not preferred to death.”

The sublime is thus experienced through overwhelming emotions, most likely painful ones. But there is a catch, or rather a sweet spot, for “[w]hen danger or pain press too nearly, they are incapable of giving any delight, and are simply terrible; but at certain distances, and with certain modifications, they may be, and they are, delightful, as we everyday experience.”

Burke makes a list of categories through which one can meet or experience the sublime, being these: terror, obscurity, power, privation, vastness/infinity, succession and uniformity, magnitude, difficulty, magnificence, light and color, sound and loudness, suddenness and intermitting, cries of animals, bitterness and stench, and pain.

Coincidentally or not, these categories or elements are precisely the same that could also describe the characteristics of a gothic romance or a horror narrative. Gothic fiction was introduced at the end of the 18th century when Romanticism was also protesting against the increasing rationalization of the world at the dawn of the First Industrial Revolution. By valuing intense emotions and idealizing all things medieval, romantics created art to make one feel, to elevate, to guide through the sublime: to sublimate or, ultimately, be sublimated.

To sublimate and be sublimated

In his treatise, Burke mentions how different languages merge both the sense of astonishment and fear in one same term, this being the sensation or emotion caused by the encounter with the sublime:

Thambos is in Greek either fear or wonder; Deinos is terrible or respectable; (…)Vereor in Latin is [to reverence or fear]. The Romans used the verb stupeo, a term which strongly marks the state of an astonished mind, to express the effect either of simple fear, or of astonishment; the word attonitus (thunderstruck) is equally expressive of the alliance of these ideas; and do not the French étonnement, and the English astonishment and amazement, point out as clearly the kindred emotions which attend fear and wonder?

While the verb sublimate is connected to the adjective and noun sublime, it may also refer to the chemical process of solid matter turning into gas without passing the liquid stage. However, in a figurative sense connected to the concept of sublime, to sublimate means:

- To refine (something) until it disappears or loses all meaning.

- (psychoanalysis) To modify (the natural expression of a sexual or primitive instinct) in a socially acceptable manner; to divert the energy of (such an instinct) into some acceptable activity.

- (archaic) To obtain (something) through, or as if through, sublimation.

- (archaic) To purify or refine (a substance).

To be sublimated, by extension, is to submit yourself to these processes. When facing the sublime, with all the fear and astonishment caused by the encounter, there are only two possible outcomes: to sublimate these feelings into something else (say, an artwork) or to be taken away by it.

Now, why would anyone want to be exposed to such extreme states? Isn’t life already too harsh these days, unwillingly? Indeed, but that is precisely why one might throw oneself into the abyss, at least if the fall holds the promise of release. The logic is similar to sex: no matter how strenuous or even painful the act might be, if it holds the promise of release, it’s worth it.

Eros and Thanatos

Yes, this is where we bring Freud. He was the one who proposed the psychoanalytical use of the verb “to sublimate”, resignifying it as a “defense mechanism that involves channeling unwanted or unacceptable urges into an admissible or productive outlet”.

I got this description from the website Psychology Today, where the example of sublimation tells that “a woman who recently went through a breakup may channel her emotions into a home improvement project.” In other words, sublimation is anything you can do to transmute pain into something else, then heal and carry on.

In Freud’s psychoanalytical theory, we, as humans, are moved by our erotic energy. However, life in society only fares us a limited amount of space to express this energy; the rest must be channeled through other outlets if we aim to be psychologically balanced. In other words, we need to sublimate these urges (or libido) into “socially useful achievements”, such as artistic, cultural, and intellectual pursuits (not to be confused with intellectualization, which… may be what I am doing now, writing this piece).

Freud’s theory is that humans are moved not only by the sexual drive (libido) but also by another one: the death instinct. He names these two impulses Eros and Thanatos, after Greek gods who were brothers and also opposites. Needless to say, they were always competing against each other, and that’s exactly how it goes in our psyche. Still, we are but mere mortals and we know too well who is the winner, so much so that we barely enjoy Eros’ harp when Thanatos is raging a rendition of the Requiem.

In practice, sadomasochism is the most obvious example of how human sexuality can blend pain with pleasure, death with libido. But it’s not the only one. There are many ways through which pain can be experienced in just the right amount, just enough to make us feel like we are being devoured, left speech- and breathless, certain that this is our last… only to suddenly be brought back to the welcoming arms of the release, of the sublime. It is about being taken away by Thanatos, only to be rescued by Eros. It is an orgasmic episode, but it doesn’t need to be literally sexual as much as it is libidinous in the sense of a life force.

But, in reality, life is painful, to an extent that it is more often than not too much to bear, too far away from the sweet spot of the sublime. Trying to experience the sublime is, therefore, an attempt to break the cycle of suffering, even if momentarily, to find the release while still being in pain. Just like the final girl in a horror movie, or more specifically, the heroine of Terrifier 2, when she dresses in the cosplay designed by her dead father and reemerges from the water tank.

To be blessed by a horrifying catharsis

I previously published an essay about how horror movies can be a means to assess traumas by putting a sort of organization and conclusion to situations that are traumatic, but still solved in fiction. In summary, the proposition is that reliving or recognizing your pain in a fictional narrative can offer a sense of catharsis.

According to M. Clasen in Why Horror Seduces (2017):

Horror movies (…) often evoke strong emotional responses, ranging from fear and anxiety to relief and exhilaration. This emotional rollercoaster can serve as a form of catharsis, helping individuals process complex emotions associated with their trauma. Research suggests that horror fans may use this genre as a way to confront their fears and anxieties in a safe, manageable way, which can lead to a sense of mastery over these emotions.

The definition of catharsis on its own is “the process of releasing, and thereby providing relief from, strong or repressed emotions.” It is thus no big leap to think that sublimating and the experience of the sublime are a form of catharsis. Being in contact with dark, deep, and perhaps even frightening topics may be not only therapeutic, as new research suggests, but also a means to find pleasure and ultimately happiness.

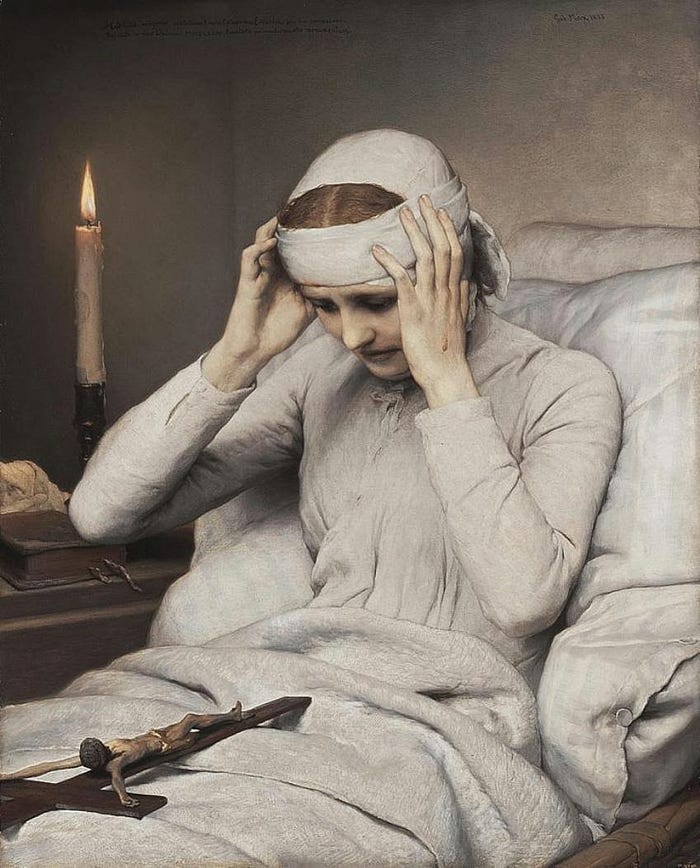

Because, yes, for some people, happiness is not a field of daisies with kittens and butterflies, but the dark, foggy woods in the sunset, when everything is quiet and eerie. In Eggers’ Nosferatu, all landscapes are melancholic and even the beach is peppered with crosses. But, most importantly, the character Ellen is seen as a woman prone to a melancholic disposition while, in fact, she is spiritually attuned, some sort of contemporary sorceress as the character Von Franz argues. Historically speaking, being mentally unstable or ill could always be mistaken for someone’s mystic or spiritual abilities — or was it the other way around?

Ecstatic sorrow

The trap in finding happiness and pleasure in all things dark is that this could ultimately be a symptom or a tendency toward mental illness. It is no wonder that such preferences or personality traits have a stigma because it could always be a medical issue rather than just the way someone truly is. I will never forget the several times a former therapist said I shouldn’t confuse my anxiety (in the sense of a clinical diagnosis) with my personality or who I truly am.

In the religious world, ecstasies, visions, stigmata, and other “holy” signs were often connected to altered states of the mind achieved by different means: praying for an extended amount of time, spinning around yourself (Sufi monks), complete isolation (hermits) and deprivation of sensations, starvation (anorexia mirabilis), meditation, the use of hallucinogenic substances (to Carlo Ginzburg, there were no sabbaths, just women getting high on mushrooms), etc. Anything goes when it’s about achieving a state of trance and ecstasy, be it for recreational purposes or in the pursuit of a spiritual and religious (reconnecting) experience — Santo Daime being the institutionalized version of the latter.

In Catholicism, mystics such as the saints Teresa of Ávila, Catherine of Siena, Rose of Lima, as well as theologians such as Hildegard of Bingen and Julian of Norwich, are known to have experienced ecstasies and visions that allowed them to become one with God. The nature of these ecstasies and visions is hard to explain, but in the book On Mysticism by Simon Critchley, we get to a more philosophical approach to these phenomena.

We learn with Critchley that trances, visions, and ecstasies don’t happen continuously in the lives of the affected, but it’s an event at a certain point in time that is so intense and remarkable that those who experience it are prone to spend the rest of their lives processing the contents. This is the case of Julian of Norwich, a theologist who devotedly prayed to be inflicted with a disease that made her suffer as much as Christ on the cross. When she finally is hit by this terrible malaise, or more specifically, after receiving the final blessings from a priest, she enters a trance that floods her dreams and grows to become her vita opus.

Now, I believe that many times Critchley overlaps the concept of mysticism with that of religious ecstasy. But, in his words, mysticism is…

A way of describing an existential ecstasy that is outside and more than the conscious self. It is about releasement and detachment, what it might mean to lead a released existence, a fluid openness, a cleared looseness, a limpid intensity, where both the concepts of mind and world or the soul and God dissolve into something altogether stranger and yet simpler: an experience of freedom which is not freedom of the will, but freedom from the will.

Critchley suggests that Hamlet is the anti-mystic as this is a character that pursues control over everything, using reasoning to tackle every aspect of his life. This tendency is so pervasive that even Hamlet’s love for Ophelia, his mother, the world, and himself, ceases to exist against such rationality. It seems that the way to go in the pursuit of ecstasy is not through rationality and the Enlightenment, but through Romanticism and the dark night of the soul, after all.

For Critchley, melancholy, woe, and misery are heavy things that stop us from experiencing the mystic ecstasy, but it is, at the same time, a comforting state as “misery loves company”. I’m not sure if I agree or follow this argument when you consider that what ignites the ecstatic experience in Julian, which is his main example in the book, is pure suffering and sickness that takes her to the verge of death. Critchley even mentions how bloody and horrific the descriptions of the ecstatic episode are, to the point that Julian’s accountings look like a horror movie. So, are we now finally convinced that horror movies are ecstatic and mystic?

Jokes aside, what the author seems to be conveying is the idea that once the ecstasy is achieved, that’s when you find the release of all this suffering, and so you’re one with God. This, however, is not really about God, but something entirely else that we (or even Wittgenstein) cannot quite name. Religions, however, might refer to it as God, whereas Lovecraft might describe it by not describing it — oh, to be a negative theologian of horror.

Critchley stresses how Julian frequently uses the adverb “suddenly” to describe her ecstatic experience in her writings. Remember how Burke listed suddenness as an element of the sublime? In Julian’s mystical experience, suddenness and subtlety blend into one single thing after physical strenuosity is sublimated into ecstasy, into an orgasm. It is no coincidence that Bernini has portrayed Saint Teresa’s ecstasy in a very erotic way (especially for the time), but it is also increasingly more understood that the Church does see the mystical union with God as an erotic, yet ascetic, experience.

In fact, the Eucharist is characterized by the union of bodies, Christ’s and the recipient of the host’s. Critchley even mentions how Christianity in the high Middle Ages had a very oral relation to Christ: “One consumes God through the mouth. To recall Madame Guyon’s words, God is all mouth. Love is eating and being eaten.”

To devour and be devoured

I had a supervisor at the university who advised me to stop seeing connections in everything when I am writing a thesis. I never listened to him, so I never stopped believing that the things (ideas, people, concepts, artworks) that I encounter are just new pieces of the same puzzle that I am currently working on.

For example, I saw this meme while casually scrolling my Instagram feed:

I have seen this same cycle being used for other memes with images from the series Hannibal and Fleabag, but I found the one above on a profile dedicated to Chaos Magick memes, so it seems that it contains a magical or alchemical perspective.

The fact that this version has the Triple Goddess in the center of the cycle reinforces such a reading as the triple figure contains Hecate, Persephone, and Demeter, or the Mother, the Maiden, and the Crone. They represent the passage of time and the change of seasons, the way everything decomposes and dies in winter to be born again in spring. But the message here is more visceral: it is through devouring, through change and incorporation in digestion, that love is born from consumption.

I am currently reading Clarissa Pinkola’s Women Who Run With Wolves, and there is an excerpt in which she mentions the tale of Bluebeard and how this cautionary tale addresses the maturity of women and how we need to be attuned to our instincts to see through appearances, to trust our gut feeling.

She mentions how the end of the story, when vultures eat Bluebeard’s corpse, creates a parallel with sin eaters, or the people who were hired to eat the sins of others so they could be purged. The role of sin eaters, as much as scavengers and decomposer creatures, is to transmute foul material. In Nordic mythology, when one dies they go to Hel, which is not a place but a goddess that is responsible for the transmutation of the deceased. The same goes for the Huesera, the bone woman, who collects the bones of wolves and sings until flesh grows and life is born.

On the other hand, the act of devouring implies an actor and a subject, unless the process is autophagic. In On Mysticism, Critchley takes a brilliant leap from mystical ecstasies to connect that with authorhood, or more specifically, the artistic or creative process.

We learn that after being affected by the visions, Julian spent the rest of her life writing and reflecting on them. Can’t this be the same for artists and writers? Perhaps we haven’t been blessed with mystic union per se, but to write and to make art are, on their own, strenuous activities that can only be fruitful or relevant if we devour our own flesh in the process, if we set ourselves on fire.

By quoting Anne Dillard’s Holy the Firm, Critchley reflects on how “there is no such thing as an artist: there is only the world, lit or unlit as the light allows.” After all, “when the candle is burning, who looks at the wick?”. Here, the wick and the artist are one, as the author explains, “insofar as they burst into flame and light up the world.”

The light that the wick/artist makes burns through sacrifice, but “life without sacrifice is an abomination” anyway. So there they are, the artist, setting themselves and their world on fire: their subjectivity, their identity, their interiority. “The writer’s life goes up in flames in the work. Or it does not. In which case, the work is a failure. When it succeeds, however, emanance and immanence are fused together into something holy and firm. Nothing else matters.”

Nothing else matters.

When you devour yourself and burst into flames, you change into your work, you become one with it, and then you are ready to love once more — love being this transcending experience that comes after self-immolation and annihilation. There it is, the mystical union between the author and the work, conjoined into one single thing that is art itself.

While the fire metaphor used by Dillard takes me back to the visuals of the Buddhist monk who set himself on fire as a protest in the 1960s, it would be more correct to make a comparison with artists that practice self-immolation as part of their performance (take Viennese Activists or Regina Jose Galindo, Marina Abramovic, etc). All in all, either you become an artist strictu sensu or you make your life your masterpiece. It’s just a matter of choosing between oil paint or dating apps.

Dopamine rushes in the era of avoidance

The digression here is not accidental but a means to the end of this essay. The very fact that I am writing this is an act of self-immolation, an attempt to bite this part of my soul out, munch it until it changes and becomes something that my readers, my baby birds, can swallow and be nourished to love again.

Critchley brings up the myth of the mother pelican pictured in medieval bestiaries, in which the bird would tear her chest open and feed her babies with blood. This is the sublime; this is the sublimation of pain into nourishment and the ecstasy of (motherly) love. It is a suffocating, desperate process. Still, as Dillard puts it, since life without sacrifice is an abomination, then not giving up on yourself may render life not even worth living. At least, for me, I would rather die in the arms of someone to whom I gave my heart and soul rather than live forever in regret and fear behind walls I put up around myself.

And there we go for the ultimate topic of contemporary dating life: attachment styles and all the games people play when simply trying to love. One thing I learned as someone with a disorganized attachment profile (both anxious and avoidant) is that anxious attachers are prone to falling for avoidants and vice versa because their fears and traumas complement each other, and they both provide dopamine rushes for each other in their dynamics.

The scriptures say that avoidants will lovebomb the anxious, who will in turn bleed their hearts out, making the first overwhelmed and then run away. Still, at some point, the runaway starts to miss the taste of blood and chase it once more, only to pull back again and be chased, and so it goes ad nauseam.

Is this our times’ version of self-immolation for the pursuit of the release of love? That I hurt myself so much and so often only to get the dopamine rush that makes me feel ecstatic? I’ve seen people argue that people are so used to this toxic dynamic that a secure person or attachment style may feel unattractive because it simply doesn’t feel ecstatic to those who are disregulated — there is no pain, no wound to be licked, healed, and torn open again. A friend once told me that passion is incendiary, but love is a fireplace. Or is it?

The pursuit of the sublime in others is a dangerous thing these days. Perhaps in the times of Shakespeare, it was more noble to kill yourself when you can’t be with your beloved instead of choosing to keep swiping right endlessly and mindlessly because you are unable to decide whether to commit to someone and consequently, naturally, be hurt again. But we are all hurt, with or without walls built around ourselves. That is where we are all leveraged — through death and pain.

And this is why I like all things dark, melancholic, intense, and dramatic: I want the taste of the sublime, and I am not afraid of pain, of bleeding, and of tearing my heart open if need be. It has never been healed, so I might as well let it be pierced over and over again until one last blade rests inside of me. I can take it. Or can I?

Love may feel scarce these days, but I don’t think it is an unrenewable resource. There is no such thing as a reserve for love, one that empties after you give too much. No, what is expended in the process is not love, but our strength, our faith and hopes, and of course, so much wasted lifetime.

But Eros and Thanatos are nevertheless forever inside of us, fighting this unfair tug-of-war that we all know is fated to be won by the latter. Only then, at the very end, can we love no more, or perhaps this is when we do reach the ultimate mystic union, the perfect sublime experience: complete and irrevocable extinction.

With that said, I hope to die artistically, in flames.